23 may 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

On the other side of the sea

Charlotte Caspers presents new work in which the blue pigments ultramarine (lapis lazuli) and citramarine (azurite) play a central role. These rare pigments hold a special place both in the natural world and culturally. During the golden age of European painting, they were prized for their vivid colour. In this new work by Caspers, these blues together celebrate the beauty of nature and symbolise the longing to look beyond the horizon, inspired by the sea. We visited Charlotte Caspers in her studio in Bergen (NH).

Charlotte Caspers (born in 1979) has a home studio surrounded by greenery near the sea. It's a fitting location for an artist whose work originates from her wonder at natural beauty. "I need stimulation from my surroundings. Even though I have plenty of ideas I want to pursue, I work at my best when my environment inspires me. To me, that's the natural world." She walks on the beach weekly, absorbing what she sees. "Light blue, shades of grey and their variability, which is also reflected in those stones."

'Those stones' are lapis lazuli and azurite. Caspers has had them in her studio for years, as they are old acquaintances from her previous career as a researcher and painting restorer. She calls them relics of the natural world. The pigments extracted from them have a similar status: they are inextricably linked to the golden age of European painting. The blue pigment ultramarine is derived from lapis lazuli, while the similarly blue citramarine is extracted from azurite. Until well into the 17th century, both were the primary inorganic blue pigments, cherished for their clear colour and often difficult to obtain.

This difficulty is reflected in the evocative meanings of the pigments’ names. Ultramarine, which is Latin for ‘on the other side of the sea’, was sourced in Afghanistan and transported to the West via Baghdad on Venetian ships. The journey is embedded in the name. Citramarine, another name for azurite, means ‘on this side of the sea’. Azurite is a deep blue mineral found in the upper layers of copper deposits.

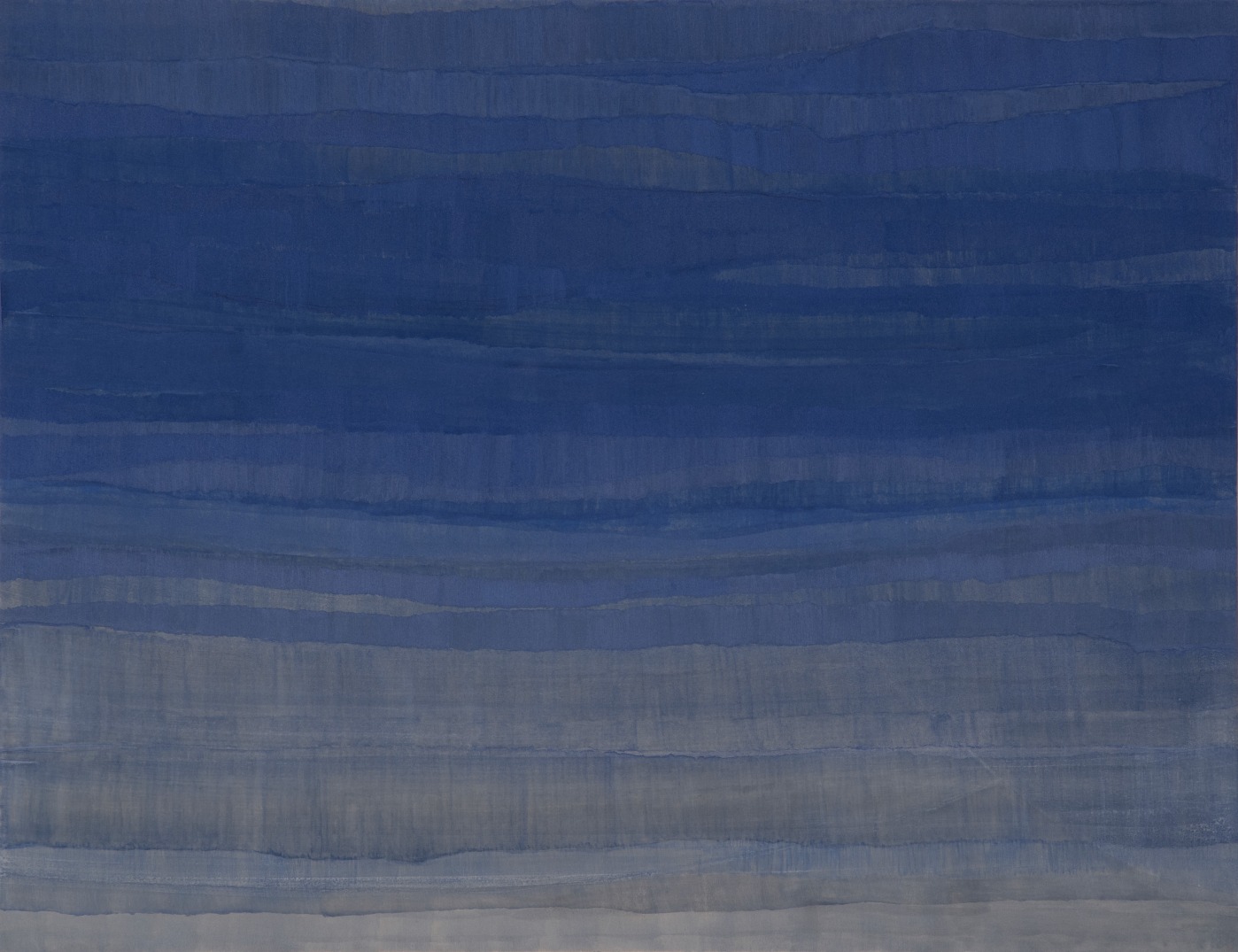

Charlotte Caspers, ultramarine, 2023, BorzoGallery

A visual language

Ultramarine and citramarine were expensive pigments primarily used for iconographically significant subjects, such as the bright blue mantle of the Virgin Mary. “The significance of the materials is very important to me. At the same time, they have their own visual language and that’s what I based this series of works on.”

By this language, Caspers is referring to the various shades of blue seen in the predominantly small panels—the smallest measuring 30 x 23 cm, the largest 66 x 51 cm—in the exhibition curated by Colin Huizing. The small sizes of the handmade oak and linden panels are due to the high production and material costs. The depth of the blue is determined by the size of the pigment particles: the larger and purer (fewer impurities), the deeper the blue.

Charlotte Caspers, azurite gr 2, 2024, BorzoGallery

In the sink in her studio are the sieves she uses to wash the pigments. In bowls of water, she separates pigment particles of different sizes and binds them into paint with rabbit-skin glue.

“The panels seem very simply painted, but some have up to twenty-five layers. The deep blue is like blue sand, but if you painted it onto a white panel, you’d have only a few blue specks. That’s why I start with several chalk layers, followed by layers of lower-quality blue, which act as a kind of net for the higher-quality pigments.”

In addition to work with ultramarine and citramarine, there are several panels with gold leaf. Caspers polishes the gold leaf with an agate stone, an ancient technique. "The gold represents light and the blue pigment represents matter. This brings us back to painting at its most fundamental level: matter and light, the pillars of my work,” says Caspers, who has been showcasing her autonomous work for about five years now. She mirrors nature in both a material and conceptual way.

Charlotte Caspers, gold I, 2024, BorzoGallery

According to Caspers, painting, like science, is a way to relate to the greatest artwork of all: nature. The relationship between art and science has been artificially severed in her view. “In science, people often zoom in closely on something small in an attempt to understand the big picture.” This is certainly not the case with Caspers. She starts from a wonder at nature and works based on her extensive knowledge of art history and historical materials and techniques. Her work is rooted in a long tradition, giving it a unique place in contemporary art.

Caspers did not attend art school, but everything she has done has contributed directly or indirectly to her current practice. After high school, she studied art history, trained as a painting restorer and made reconstructions for museums for years. She has also been interested in the natural world from a young age, even though it was far away from the new housing estate where she grew up. As a child, she had to rely on her imagination. “I collected stones and shells, laid them out in my room, picked up a stone and travelled by imagining where it came from.” Caspers is traveling again now, to the other side of the sea.

Charlotte Caspers, woad, 2023, BorzoGallery

Ultramarine – Citramarine with work by Charlotte Caspers opens on 30 May at 5 pm at BorzoGallery in Amsterdam.

Ultramarine – Citramarine was curated by Colin Huizing and the publication of the same name is available at the gallery.

On 31 May and 1 June at 4 pm, Charlotte Caspers will be holding an artist talk in the gallery. Curator Colin Huizing will also be present.