03 april 2024, Wouter van den Eijkel

The price of a pearly white beach

What do Wijk aan Zee and the Tuscan town of Rosignano Solvay have in common? Aside from both being seaside locations, a highly polluting factory is their largest employer. In Tuscany, this leads to an Instagrammable, pearly white beach with stunning azure blue water in the bay, but the price paid by the local population and nature is steep. There is another similarity between these places: they are both the subject of TINKEBELL.'s work. Until 13 April, 'Arena Candidus Solvay' will be on display at TORCH Gallery.

The first thing you notice when looking at the satellite images of Rosignano Solvay on Google Maps is that the sand is much whiter and the water considerably lighter blue at the Spiagge Bianche (white beaches) than at the surrounding beaches. But the reason is not as nice: a cleaning product factory owned by the Belgian chemical company Solvay has been dumping chemical waste into the river that flows from the factory to the sea for years.

TINKEBELL. was still working on her series about Tata Steel (Flora Tata Metallica, 2021-2022) when she read an article about a beach in Tuscany that was completely white because it had been bleached by a factory's emissions. Influencers would go there to take pictures as if they were in the Caribbean. "The photos looked photoshopped, but if it was true, it would be a kind of white counterpart to Tata, where the emissions were black." It's a comparison that emerges repeatedly in the works of art in Arena Candidus Solvay.

The first time she went to Tuscany was at the height of summer. It was a bizarre experience. And true enough, the beach was a snow-white colour and the water a stunning azure blue. It was crowded, the beach was full of bathers, there were ice cream stands and souvenir shops – she bought a snow globe of the Spiagge Bianche – and the river was cordoned off. Yet people were swimming there anyway.

A white plastic bag

Like the work in Flora Tata Metallica, all the work in the series Arena Candidus Solvay is made with materials found on site. She initially planned to work with the sand from the beach, but it didn't turn out as hoped. She then tried river water evaporated on black cloth. That didn't work out either. So, she flew with 20 buckets to Tuscany to filter the water. She stood in the middle of the river filling the buckets with the most concentrated water, but sank up to her knees in the mud. "I thought there was some kind of white plastic bag that was released. I discovered that I could grab through it." The waste turned out to be heavier than soil and was stored under the sand of the riverbed. " I filled several buckets with the stuff and let it dry. I then ground it to use for these works."

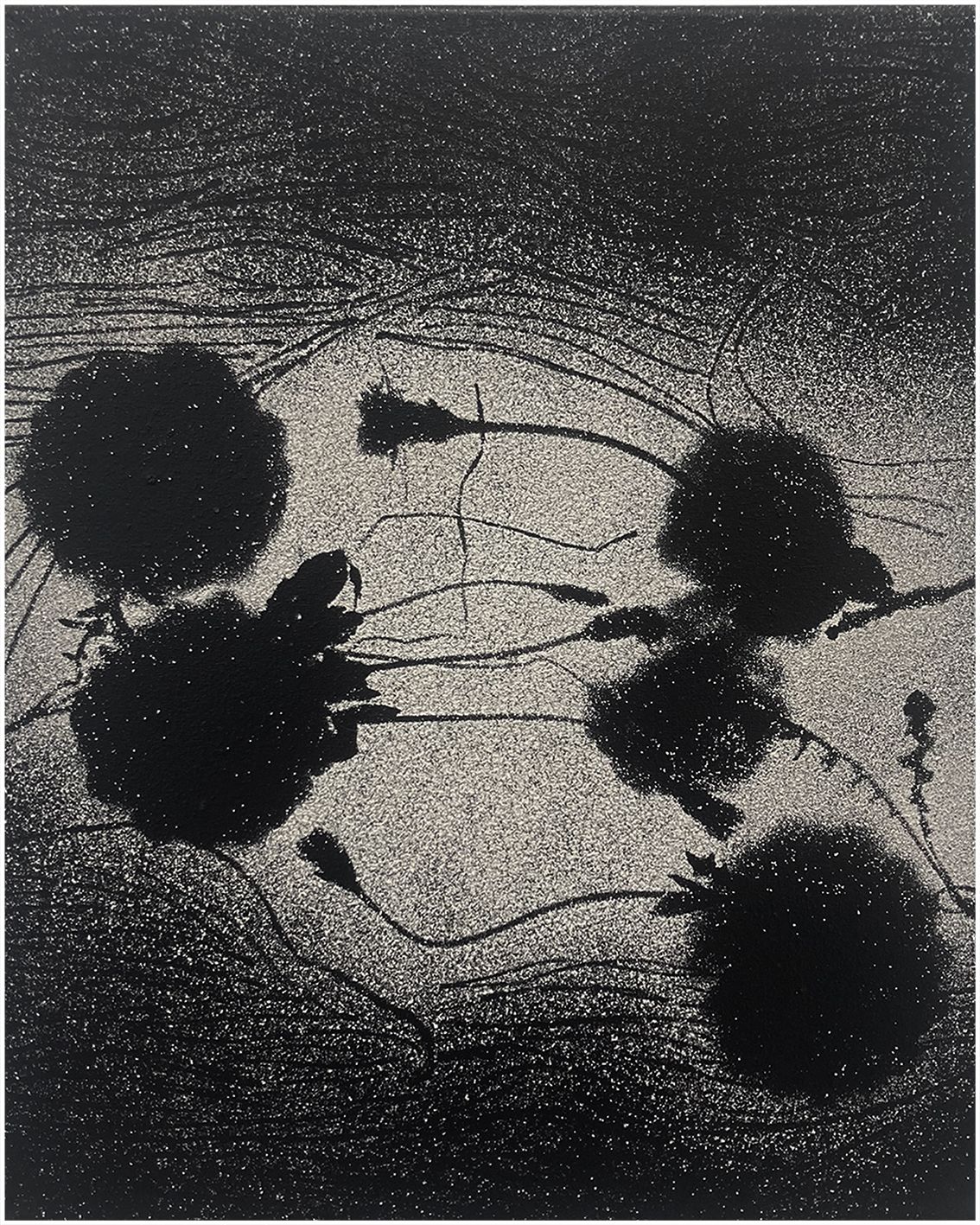

But the discharges into the river are not the most polluting emissions from the factory, which come from the chimneys. In order to protect the population somewhat and remove the worst emissions from the air, Solvay has planted about a football field's worth of pine trees between the factory and the centre of the village. "That's important because the health reports from the area are comparable to those of the IJmond region. There are lots of people with cancer, heart disease and neurological disorders. The pine trees are a band-aid solution." The new work shows prints of the pine needles, cones and weeds that she collected at the Solvay site. "My canvases are protection and pollution in one."

“They're listening”

You might expect that emissions and poor health would be hot topics in Rosignano Solvay, but the emissions are barely a subject of conversation. The local population is almost entirely dependent on the factory. Social cohesion and control also play a large role. In Wijk aan Zee, social cohesion is also strong, with families that have been working at the blast furnaces for four generations and deriving their identity from it. But unlike the surroundings of Rosignano, finding comparable work in the IJmond region is relatively easy.

Solvay also seems to operate much more intimidatingly than Tata Steel: “When I talk to people in Rosignano Solvay, they say they don't want to talk about this in public because ‘they're listening and there will be repercussions’, whatever that means, but people are genuinely afraid.”

No dialogue yet

Whereas after Tata Flora Metallica, a dialogue was initiated with Tata Steel's CEO Hans van den Berg – Tata bought two works, one hangs in the entrance to the factory, the other in Van den Berg's office, clearly visible during online meetings with the parent company – a response from Solvay is still pending. "I can see that they have looked at my LinkedIn profile and I'm connected to the director of the factory. I invited him and told him he should buy a work as a reminder of his responsibility for the environment."

With Van den Berg, she has agreed to expand her series over the next five years with art series on the emissions from several factories around the world. In the meantime, Hans van den Berg promises to solve the problems caused by Tata Steel in the IJmond region. Tata's solution is being cast into a manual, a blueprint that other large industrial concerns worldwide can use for a clean and sustainable future.

You can't Google everything

Future projects will all revolve around heavy industry, around factories that opened their doors some 100 to 150 years ago and are still in operation, but which cause problems for local residents. The series will inherently seem to embody a degree of duality. Opposed to local values and interests such as employment, social cohesion and pride, there will always be larger, less tangible power factors, such as regional, national and international economic interests and (geo)political power dynamics. It is a field of forces in which the interests of the local population, to which the environmental and health damage is passed on to, are rarely taken into account.

The next project is likely to focus on the oil industry in the Niger Delta around Port Harcourt, Nigeria, but this requires travelling to the location because you don't know what you'll find beforehand. "Stories that are interesting to me can't be Googled." Sinking into the river was a coincidence and the magnetism of Tata Steel's emissions was not widely known. "Residents told me that the RIVM advised sweeping the black dust off the windowsills with magnets. Of course, that doesn't just apply to windowsills. I tested it with a magnet in the sandbox of a playground. The woman who lent me the magnet turned white as a sheet on seeing the effect."