21 september 2023, Flor Linckens

Kyle Weeks: A Collaborative Approach to Photography

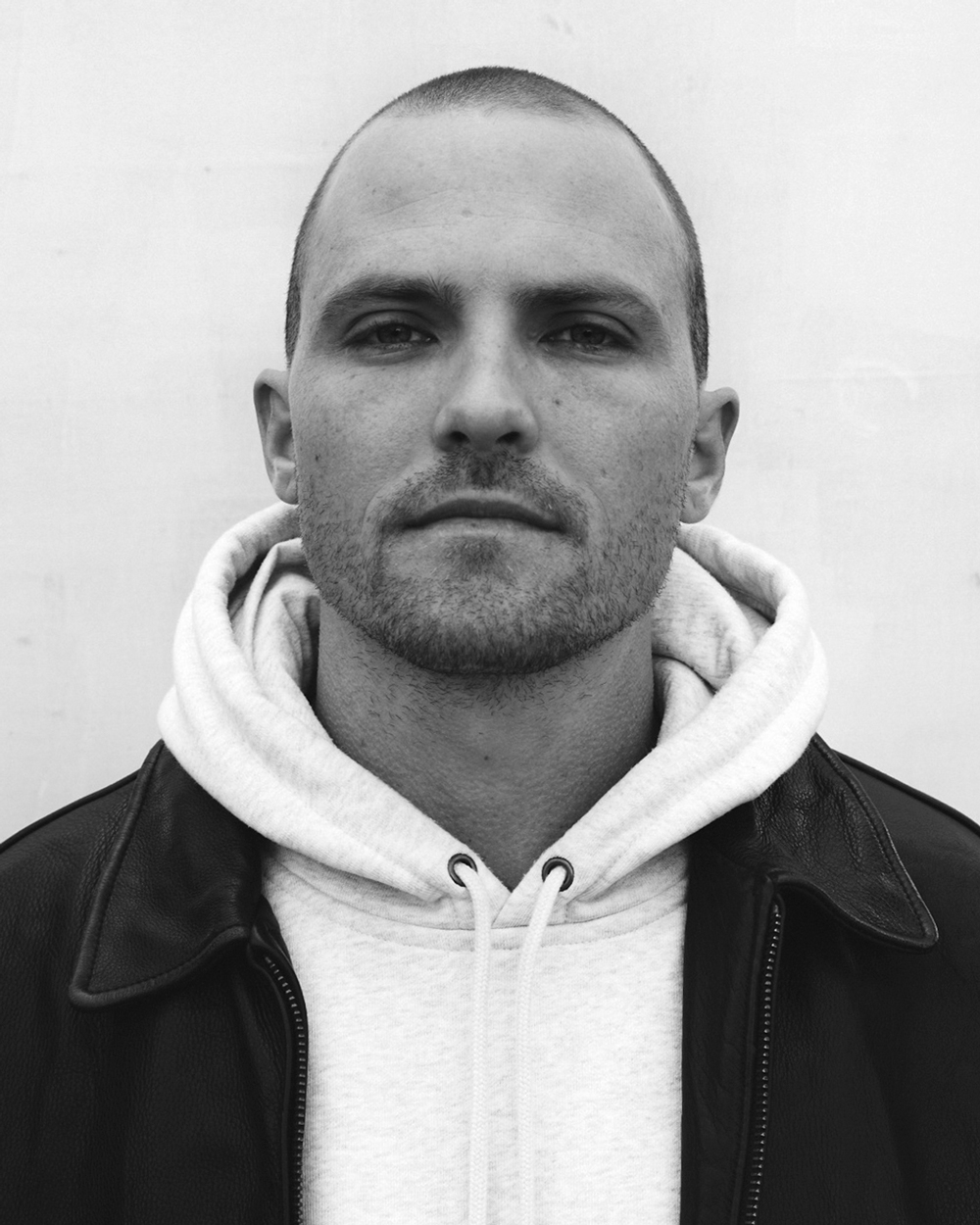

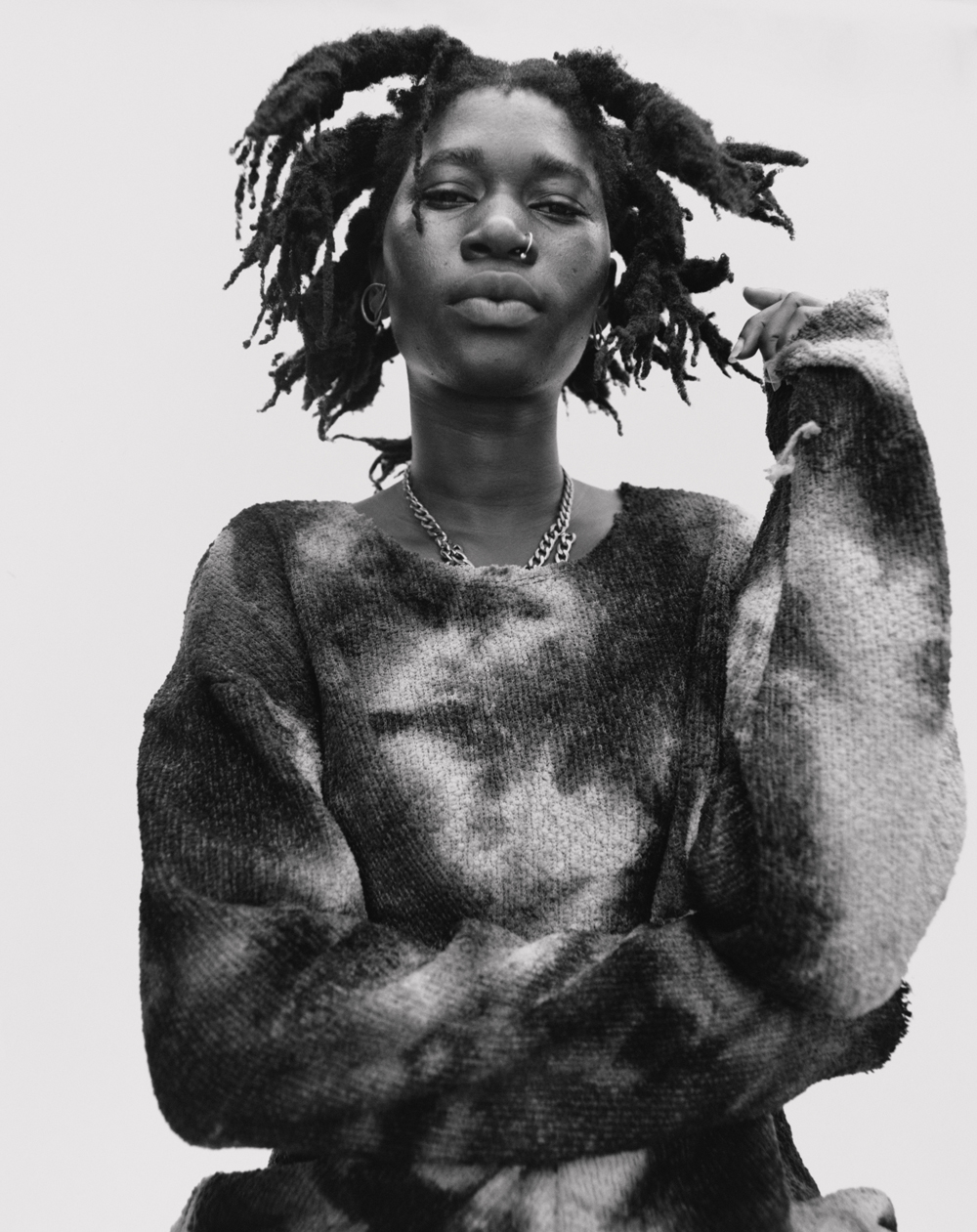

At Unseen, Galerie Gomis (previously Galerie Number 8) will show work by Kyle Weeks, a photographer who explores themes of cultural transformation, social identity, self-expression and representations of the African body, visualised in vibrant portraits of young Ghanaian people. Explore his work in the Unseen fair catalogue.

Weeks was born in Namibia to a German-American mother and a South African father and spent his childhood there. At the age of 19, he relocated to South Africa to study Photography. His work is marked by a keen awareness of his own position as a white man in Africa, which influences his ethical considerations and artistic resonance. Weeks' first visit to Accra in 2016 left a lasting impression on him, a bustling city in the midst of a cultural revival. Over a period of six years, he staged portraits there during month-long visits. The result of this six-year project, "Good News," was recently launched as a photography book at Huis Marseille in Amsterdam. Growing up with many negative and misrepresenting portrayals of Africa in the news, Weeks aimed to create "Good News" as an empowering and positive representation of Ghana, through youth culture and style, using the power of photography to actively challenge and shape perceptions.

He also empowers his subjects in a more literal way: 50% of the print sales directly finds its way back to the people that were photographed. Weeks: “The decision to redirect 50% of proceeds back to each person depicted in the sold photograph, is a way to bolster the idea of empowering imagery. Most of the depicted young people are aspiring to further their craft in their respective fields be it music, fashion or skateboarding and ultimately need financial resources to do so. This incentive will hopefully enable these youth, offering resource to develop their voices in their respective fields.”

Weeks’ dynamic and energetic work considers historical and colonial power dynamics and offers a fresh perspective. He is conscious of the problematic history of white photographers documenting Africa and takes a slow and more collaborative approach instead. It involves full consent and a true collaboration with his subjects, building relationships and ensuring that he represents them as they see themselves. In doing so, he deals with persistent stereotypes as well as the traditional power dynamics of picture-taking. Weeks is interested in their unique frame of reference, which is far from any western gaze.

Weeks: "My upbringing in Africa has had the most profound influence on my artistic practice and vice versa. While questions of belonging have lingered since being a teenager in Namibia, making photographs has allowed me to grapple with my own position of being an African of European decent. It’s a unique position from which to create work and although it can be difficult to navigate, I decided that it was a narrative that I wanted to contribute to."His portraits of young people in Ghana emphasise style as an important aspect of self-identity in contemporary cities in Africa, a continent that is far from a monolith in many other respects. In doing so, Weeks is inspired by the post-colonial African studio portraiture of photographers like James Barnor, Malick Sidibe, Seydou Keïta and Philip Kwame Apagya — and Weeks makes sure to credit them in his photography book. His work is also influenced by The New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), a style from the 1920s that followed — and challenged — Expressionism and aimed to be more objective, limiting the point of view of the artist and effectively imbuing more power and agency into the subject instead. Weeks does not aim to portray people in a certain or preconceived way. That is significant, because his work is a departure from the static nature of the traditional ethnographic photography of many white photographers that preceded him, who often depicted the people in front of their cameras in ways that suited them.

Weeks: "Portraits are by nature the result of relationships. This then begs the question, how does a photographers proximity to the subject shape the working process and resulting imagery? A question that I’ve let guide me and found particularly interesting considering my own context. In previous projects such as the "Ovahimiba Youth Self Portraits" as well as the "Palm Wine Collectors", this relationship became the focus of my working methodology as I tried to employ a number of strategies to mitigate the power imbalance that historically rests mostly with the white male photographer. Later, once I decided to pursue the project in Ghana, I again wanted to employ a sensitive, collaborative approach to depicting the nuanced and multi faceted nature of the youth who are shaping the future of their country. As contentious as the idea of artistic intention can be, I firmly believe that my intention to make empowering imagery from within Africa shapes my approach to portraiture.”

Weeks graduated from the Stellenbosch Academy in 2013 with a BA in Photography. His editorial and personal work has been published in various publications including i-D, Dazed, Another Mag, the WSJ and Time Magazine. In 2016, he received the Magnum Prize and in 2019, he was named amongst The British Journal of Photography’s Ones to Watch.

Weeks: "Winning the Magnum Award in 2016 helped propel my work to a wider international audience. I was still living and practicing photography in Southern Africa at the time and felt quite out of touch with the larger global industry. The exposure gained from that award helped me tap into a global network of photo editors and art directors which led to more commissions and ultimately helped kickstart my photographic career. Similarly, being named by BJP as an upcoming photographer a few years later has helped me maintain relevance and grown my audience once more. In a sea of imagery and image makers today, these awards and nominations are a great way to get your work to stand out.”