12 september 2023, Flor Linckens

Revealing and hiding: a glimpse into the darkroom of Dirk Braeckman

At Unseen, GRIMM will present work by Dirk Braeckman, a leading Belgian artist known for his cinematic and enigmatic black-and-white photography. In his own words, he highlights 'anti-spectacular' subjects: desolate hotel rooms and close-ups of anonymous body parts, curtains, elevators and pieces of furniture that he frames in a remarkable way. The suggestive and subjective works appear personal, but at the same time, they don’t function as an invitation.

In an interview with the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Braeckman states, “My work is more about hiding than showing. I am not a storyteller, I am an image maker.” He is therefore not so much concerned with capturing reality as with manipulating the image and creating a multitude of possible interpretations and layers of meaning. For his practice, the artist draws from an extensive archive that he has built up over the past forty years. Used film can go untouched for years, and Braeckman thus creates a significant distance between the moment of shooting and development. Furthermore, he’ll only date his work after it has been developed. The images are often stripped of their original context, time and narrative, which only increases the distance between the viewer and the maker.

Dirk Braeckman © Heleen Rodiers, 2018

Braeckman studied Photography & Film at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (KASK) in Ghent, but initially showed an interest in painting, inspired by photorealist painters such as Gerhard Richter. It resulted in the mindset of a painter who primarily uses photography as a starting point for the artistic process. But Braeckman prefers photochemical processes over paint and the darkroom plays a central role in his practice. In an interview with Fotomuseum Antwerp, he describes his first visit to a darkroom as “magical, and it still is to this day.” After a long visit to New York in the 1990s, his work became more and more autonomous and he began to play with the reproducibility of the medium. His shyness also forced him to partly shift his subject from people to inanimate objects.

Braeckman frequently experiments with chemical processes, examining the materiality of the image. His mostly monochrome work is characterised by a skillful manipulation of lighting, tonality and (layered) texture. But the artist reserves an important role for coincidence and spontaneity. Sometimes he takes photos of edited images in the darkroom, imbuing them with a certain meta-quality. At the same time, they are all related to the same negative. Sometimes, he combines new narratives from two separate negatives that have no relation in terms of content. The use of matte shades of gray ensures that part of the information is withheld and that the shown reality is manipulated. Braeckman's shots often contain a highly reflective flash that highlights elements in the image, which are subsequently concealed in the darkroom. The artist prefers to work with an analogue Contax T2, a heavy and automatic camera with manual functions and a high-quality lens. In recent years, Braeckman has also made use of digital techniques as well as video.

Dirk Braeckman, L.N. L.S.22, 2022, Courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York

Your practice seems to embrace a certain amount of spontaneity and chance, but at the same time, the darkroom is a place where you can exercise a significant degree of control. Do you still get surprised in the darkroom?

Constantly. Every single day, because the amount of coincidence seems to be inexhaustible in a practice like this. You can, of course, provoke some kind of coincidence. The longer I work in the darkroom, it’s been 40 years now, the better I know that certain things can happen. I can predict and direct that up to a degree, but you can never control the end result, that remains largely a coincidence. It surprises me every day and that’s also what makes it so interesting and fascinating. And it’s not just the case in the darkroom. It can also happen during shooting, especially when I shoot analogue. Occasionally, I develop and scan the film and only then do I see what happened. I can also provoke coincidence while shooting. I might know which direction I'm going in, but never precisely. But I try to avoid controlling the result as much as possible.

I also work digitally now. That's a completely different way of working. You can instantly see what you are doing on the screen of your camera. But you can actually do the same with that. You have immediate results that you can respond to.

Your works generally don’t allow the viewer to truly know them, but you do like to work in the darkroom in a physical manner, without the use of gloves. Does that make your works more personal, in a different way?

More personal… I don’t think so. It’s just that I can't work with gloves. I have to feel the material. Gloves create a certain distance between the material and your feelings. You could say it's more personal in that regard. In the darkroom, things are happening so fast, and all at the same time. It means that I don't really have time to put the gloves off and on. I'm lucky that I haven’t experienced any negative consequences / allergic reactions — at least I don't think so, up until now. Most people experience that immediately, but I haven’t. So that hasn't stopped me, even though I know it's not the healthiest way of doing it. I did pay particular attention to it when building my darkroom, I invested in a heavy duty ventilation installation. I want to be able to rely on that. Because that way, I can be in there for a longer period of time without having to go outside, so I can remain in the flow.

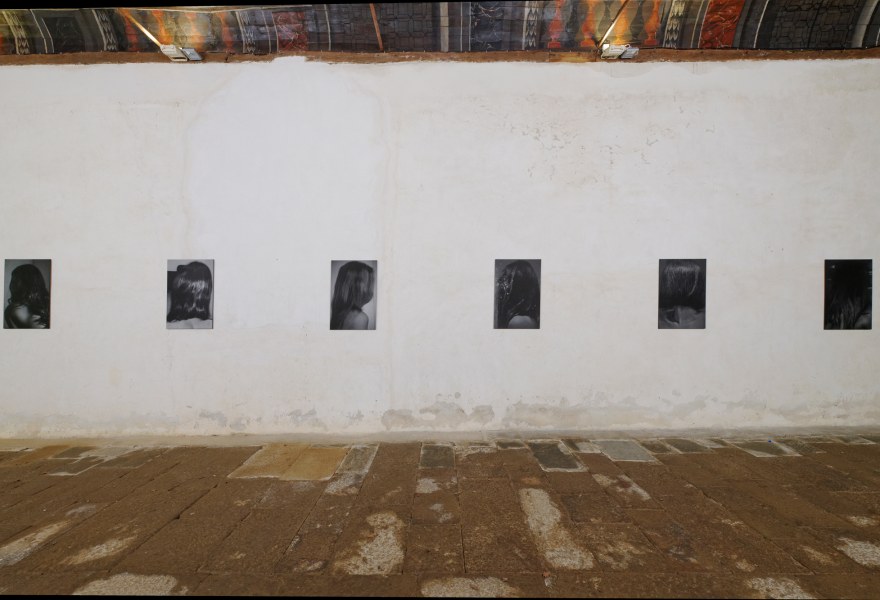

Dirk Braeckman, L.K. L.S. 22, 2022, L.L. L.S. 22, 2022, Courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York

How does the application of digital photography differ, for you, from working with analogue techniques? Are there any new techniques or equipment that you would like to explore or integrate in the future?

There is a big difference. Analogue [photography] is my tool, with which I learned to discover the medium. From the beginning, it was analogue, it’s how I familiarised myself with it. It’s completely different from time perception. Especially when shooting, you have to wait until your negatives are ready. I sometimes go the extra mile because I keep some films or negatives for a very long time, so that the surprise is even greater when I do develop a film or when I use or view a negative years later.

I only add the emotional / artistic layer to the piece during the printing process. That's why I never date my photos on the film, but only when I make the print. That way, the time and place of recording no longer play a significant role — even though that is often the case in photography. For me, the place is in my darkroom, and the date when it comes to paper, when it’s printed. Then, the work is actually finished.

Analogue and digital constitute a very different way of working. It’s almost a different medium. I don't have any new techniques or equipment in mind right now that I want to explore, but it could happen. The techniques that currently exist are challenging enough. Especially when you start to combine the digital and analogue. There are plenty of options for what I want to do. I often look for equipment and techniques to create the images that I roughly envision in my mind. Not the other way around, it’s not a matter of ’I want to test it out and see what it offers me'. No, what I need determines which equipment and techniques I end up using.

Dirk Braeckman, L.I. L.S.22, 2022, Courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York

You are currently archiving your work and your daughter is in the midst of setting up a foundation. At the risk of asking an existential question: how do you hope to be remembered in 50 years?

I don't do all this archiving with the thought of how I want to be remembered, but rather with respect for my oeuvre and my descendants. With respect to the community that has supported me over the years: sponsors, collectors, gallerists, everyone who has had anything to do with it. I'm not necessarily concerned with how I want to be remembered.

This may be a strange thing to say about myself, but I'm sure I've had a lot of influence on photographers, both nationally and internationally — especially with the advent of the internet that allows for information to spread more easily.

I don't mind people being influenced by me. Of course, you have people who copy on form: large, black and white, dark, but who lack essential elements such as the power of the overall picture. Sometimes, I can see a lot more similarities in the work of people who work with bright colours, rather than someone who makes dark photographs in black and white. Or even people who paint or make music, I can feel even more affinity with them. But that is of course difficult to explain.

In fact: I really hope for nothing. But if I do have to answer that question: I hope they describe me correctly in art history. Who I have been influenced by and who I have influenced in turn. That is enough. For the rest, I am not concerned with my ego.

Braeckman's work has been shown at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, BOZAR in Brussels, S.M.A.K. in Ghent, Fotohof in Salzburg, Museum De Pont, Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, Whitechapel Gallery in London, Museu de Arte Moderna in Rio de Janeiro, De Appel in Amsterdam, WIELS in Brussels, Palais du Tokyo in Paris and Museum M in Leuven. In 2017, he represented Belgium at the 57th Venice Biennale. His work has been included in various collections, including those of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, Kunstmuseum Den Haag, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the M HKA in Antwerp, the Ministry of the Flemish Community, Mu.ZEE in Ostend and S.M.A.K. in Ghent. He also made a permanent installation for the Royal Palace in Brussels and in 2005, he received a Cultural Prize of the Flemish Community.