24 june 2022, Manuela Klerkx

Q&A | The soundless dialogues of visual artist Zaida Oenema

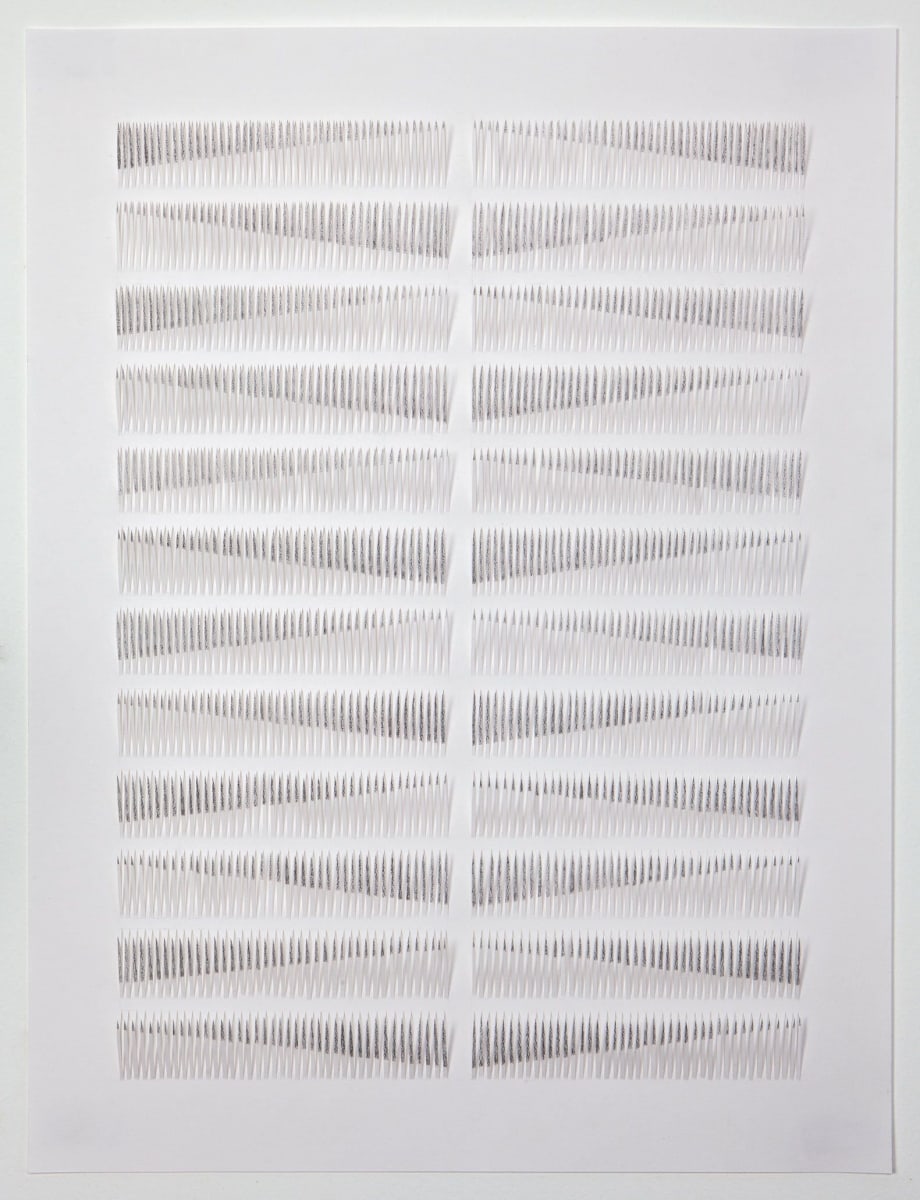

In the catalogue of the 2018 Paper Biennial at Museum Rijswijk, art historian Frank van der Ploeg calls the works of Zaida Oenema 'mo(nu)ments of silence'.* Oenema herself speaks of 'soundless dialogues'. Whether she tackles the paper with a scalpel to create waves, or with a soldering iron to burn holes, her works invariably stem from an individual desire for silence: 'not as pure abstractions, but rather as soundless musical scores.’ I asked her what she meant by that and why she quit photography to start making reliefs or, as Alex de Vries** puts it: 'spatial drawings with a sculptural quality that have a landscape-like quality, like hairs or culms that stand up in the wind'. An interview about the meaning of silence and focus, light and time, undercurrent and melody - for both the artist and the viewer.

MK Did you always want to be an artist?

ZA From childhood on I wanted to be a photographer, but an art photographer. Once I was a freelance photographer, after finishing the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, I had enough assignments to make a living, but it didn’t feel right. The need to make free work became stronger and stronger. That's why I decided to go to the Academy for Art and Design St. Joost where I did a Master in Photography without wanting to focus on photography itself. The KABK was quite a technical art school where students were not encouraged to think in terms of cross-over disciplines. At the St. Joost I took a more conceptual direction and mainly made video performances.

MK Yet you didn't become a photographer nor a video artist.

ZA After a few years, I had enough of all those screens. I missed working in the darkroom and felt like making photo prints again, and working with my hands. Moreover, I developed RSI problems from the countless hours I spent behind a screen, and since then I cannot sit in front of a screen for more than two hours. To get rid of these complaints, I literally went into the woods with pencil and paper to find and draw the jouissance, the pure pleasure or enjoyment of a simple walk in the woods. This eventually resulted in a series entitled 'Yearning', which was literally a search for life in open air, for pure, childlike pleasure, far away from all the hustle and bustle related to daily life. In the course of time, my drawing expanded and started to include various processes such as cutting and burning.

MK I have the impression that your work has become more three-dimensional over time, is that right?

ZAYes, that is correct. Space or spatiality is important to me. For my reliefs, I use the movement of light by working on the left or right side in my studio, so that the light enters in different ways. By playing with the surroundings, my work becomes mobile.

MK How would you describe your work process?

ZA On the one hand, I work from a very structured basis, while on the other hand, I work in a very organic way. The structural side consists of a grid through which I cut strips or a kind of wavy movements or burn right through. I like the contrast between the structure of the grid and the playfulness of the rhythm as a result of the movement and repetition of the human hand. I make as little use of a ruler or grid as possible. I measure out the basis beforehand, and then I am going to cut or burn without a premeditated plan. This leaves a tension as to whether a work will succeed. This way, my work process is partly based on chance, on unexpected twists that I do not think up in advance nor exclude along the process.

MK How does the right balance between the grid and the moving lines come about?

ZA I have to be hyper-focused to make my work as 'error-free' as possible. In this focus, I look for moments of emptiness, of stillness as moments of rest in the plane. Sloppiness or 'incorrectly' burnt or cut pieces then disturb this rest.

My eyes must be able to wander or scan over the surface as if looking for a horizon that is not there. With my eyes I scan the surface, as it were, as a concentrated way of observing. I see my work as a score consisting of a continuo, or the basis - the grid in my case - over which the melody weaves itself with my hand that cuts and burns and provides the right vibration. The concentration or focus of an artist such as Agnes Martin is contained in her work. That's what I strive for as well: I want people to feel the focus when they look at my work and therefore, just like myself, start to wander with their gaze and their thoughts.

MK What do you find more important? Beauty or process?

ZAI find beauty a difficult concept because what I find beautiful, someone else may find unattractive. But if I have to choose, I think the process – at least for me - is more important than beauty. I want people to experience my work as beautiful because of the process behind it. I think aesthetics are very important, but I only experience them after the work has been finished for some time. Only then do I see whether the small 'mistakes' (the flaws, as Agnes Martin called them) disturb the image or add to it.

MK How do you find out?

ZAIf I can look at my work like I look at the sea, I am satisfied. If I don't experience the mistakes or irregularities as disturbing because the unity predominates and my eyes can wander smoothly over the surface, then the work is in balance for me, which means that I am able to experience it as beautiful.

MK How long does it take complete a work of art?

WCThat can be a process of months in which I constantly have to make choices. ‘Time is of Essence' is a large work that has been exhibited in the CODA Museum in Apeldoorn and that cannot be seen at a glance. It therefore invites the visitor to stand in front of it for a longer period of time. I like the idea that my lengthy work process also results in a lengthy viewing process.

MK How do you want to inspire the viewer?

ZA When I was in the USA for my solo, a man approached me and saw all sorts of things in my work that concerned him as a writer. I could fully identify with everything he saw in my art. That is a very special experience. I am always happy when people say 'I just kept looking at it'. I consider that to be a 'wordless conversation' between the work of art and the viewer, and I often hear from people that they experience a certain peace at such a moment.

ZA No, although I do like geometry and structure and I do like to look at their imagery. I sometimes get even close to it. Having said that, I allow myself much more movement and coincidences than a formal artist would. MK What inspires you?

ZA I can work anytime as long as I don't go into a production mode. What drives me is the silence and the peace of my workplace where I am free to make whatever I want.

MK How do you see the future as an artist?

ZAI work quietly but steadily and I am fully open to collaborations with galleries and other parties abroad. I would also love to see my work hanging in a museum in a green environment, like Museum Voorlinden. Currently I am working with a gallery in the US and in The Hague and I would love to have another one somewhere in Europe. I would also like to make time for a residency. I love empty landscapes and I would like to do a residency in Iceland, for example. Now I visit such landscapes too, but in accordance with the wishes of my family. And although that is fun too, I am looking forward to a period in which I can make art in complete freedom. On the other hand, limitations force me to use my time well, and to make the right choices.

After a busy year with two solo exhibitions in The Netherlands and abroad and several large commissions, I am looking forward to a period in which I can keep my diary as empty as possible, so that there will be enough time left for reflection and research.

* de Ploeg, Frank, Paper Biennial 2018, Catalogue Museum Rijswijk, 2018 ** de Vries, Alex, Weten wat je ziet - dertig atelierbezoeken door Alex de Vries, selected by Mr Motley, Publisher De Zwaluw, 2022